Black Bart

By Michael E. Lane

Our exemplary Historical Society has embarked on a wonderful project to restore its nineteenth century barn at The Southworth House. During construction, a small room under the stairs was “discovered” that had some children’s furniture in it. Shirley Price stopped in my office one day and showed me a picture of it and asked if I knew about it. I said yes, it was a secret “hideout” we used when we played games like “Black Bart” as kids. While I do not have a particular recollection about the furniture, I well know the little room, having been in there many times as a youngster. Deborah Fisher asked if I would write about it and this is the result.

During the holidays I like to watch the movie A Christmas Story about the little boy “Ralphie” in the 1940’s and his quest to receive his ultimate gift—a Red Ryder BB gun. In one scene he dreams his house and family are under attack by a group of bad guys coming into the backyard, and Ralphie, dressed in his best cowboy outfit, drives them off by shooting them in the pants with his Red Ryder.

I always laugh and enjoy it because it reminds me of when I was a little boy in the late 1950’s. I was eight or nine years old, and a small group of neighborhood boys would frequently meet over at the Simpsons’ house (The Southworth House) after school to play with Monty and Tom Simpson. The house was central in the village, and had a wonderful yard and barn. When outdoors, we would play boys’ games like cowboys and Indians, or cops and robbers. One game we called “Black Bart.” Black Bart was an historical figure who was a stagecoach robber, but we did not know that then, only that he was a bad guy.

The Simpsons had quite a stash of toy guns, everything from cowboy six shooters to plastic army rifles. There were a couple of cap guns but I do not think there were any BB or pellet guns–nothing that really shot anything. Monty (George Montgomery) Simpson was three years older than Tom (Thomas Southworth) Simpson and I. He and the older boys would team up against the younger boys. They would always claim first pick of the toy guns and leave those less desirable for the younger ones.

As I recall, we would play “Black Bart” for an hour or so. One of the older boys would assume the role of Black Bart (usually Monty) and the other older boys would be his gang. We would start and the younger boys would hightail it to get away and hide. Soon after, the older boys would give chase shooting (or rather clicking) their toy guns at us and we would struggle to shoot (click) back.

The younger boys would usually head for the barn where there was a hideout. Entering from the basement door on the east side of the building, there was a ladder on the south wall that went up through a trapdoor into a little room under the stairs. The stairs led from the first floor to the second floor. [One might think a little of Harry Potter’s “cupboard under the stairs.”] We would lock the trap door from above. Soon Black Bart and the others would arrive, shoot (click) at us through the cracks. Finally, they would get at us through the opening between the stairs and the south wall on the first floor. “Bang Bang, you’re dead!” “No we’re not!” “Yes, you are! We win!” and the game would end.

Soon Mrs. Simpson would step into the yard and call for her boys to come in to get washed up for supper. Into the house they would go, and that was our own homes, ending a short but fun afternoon.

—————————————————————-

Edward Griswold – The Father of Dryden Village – Part 1 of 2

By David Waterman

The title “Father of Dryden Village” was applied to Edward Griswold (1758-1843) by the writers of The Centennial History of the Town of Dryden (published 1898). They deemed he deserved this title for his active role in ensuring that Dryden village would be situated in its present location in the valley, rather than at Willow Glen. He conveyed nearly ¼ acre of land on the four corners of the village to “The Good People of the Town”, on which was established the Presbyterian Church, where his wife and son were charter members, and later the Methodist church as well. Mr. Griswold also donated 40 acres of land to a blacksmith, in order to convince him to reside in the village, and he provided an acre of land for a public graveyard “[so] that all sects and denominations have the privilege of burying their dead.” This graveyard, off East Main Street, is now called the “Pioneer Cemetery”. At the time of the Centennial book, it was described as “a second wilderness… likely to be entirely forgotten,” but thanks to Leland Tripp, Walter Hunt, and Bob Watros, it was restored in 1966 and is a must visit today. Looking at the old gravestones, one may note that in those days of fresh air, exercise and natural foods, people could live to a very advanced age, if they didn’t die first.

Nineteenth century history books generally contain glowing accounts of pioneers venturing west, seeking a better life and taming the wilderness. The information we have on Edward Griswold in Dryden is of that vein. Griswold, it is claimed, “was early a sea captain”, but after the war “his wife, Asenath (Hurd), prevailed upon him…to abandon his sea- faring life and cast his fortunes in the undeveloped West”. He is described as honorable and upright, though short and thick-set in his make-up. He first came to Dryden with his son Abram and daughter Asenath probably in 1802, before other members of the family, and constructed a plank house near Lee Road. An industrious man, he established four orchards and built a cider mill, and had a sugar bush, producing up to 1000 lbs. of maple sugar each year. He also raised a great deal of stock, hogs, calves, sheep; also corn and wheat. His market was Albany, a long way to take his goods by wagon. He would return with merchandise for Parley Whitmore, Dryden’s early merchant, druggist, postmaster, justice of the peace, and scrivener, who seems to have been somewhat financially dependent upon Edward Griswold.

It is reported that, though he could reckon up the price of a load of wheat as quickly in his head as others could with paper and pencil, Edward did not know how to read when he was married, but learned from his wife, so as to be able to read the scriptures. He had a stand on which lay his Bible; and when he came in tired, he would generally sit down and read. He read slowly and would always read partly aloud, but only for his own benefit. Every word had an affix, uh as in and’uh we’uh, etc. There exists one hand-written document at the Dryden Town Historical Society attributed to Edward Griswold. It is a sermon for the Presbyterian Church on the subject of, wouldn’t you know it, industry.

The deed to Edward Griswold of Lot 39, including the northeast quarter of Dryden Village, is dated October 16, 1805, conveying six hundred forty acres for a consideration of $2,250.00. It was said that he must have been prosperous, and a man of considerable means for those days to have paid that much, which then brings up the question of his backstory. What events of his past made this man wealthy, industrious and civic minded? What was his Revolutionary War experience and why did he choose Dryden to move to after the war? This part of his story has never been detailed and will be the subject of part 2 of this two-part series on Edward Griswold, to be continued in the next DTHS newsletter.

To end part 1, regarding Edward Griswold’s life in Dryden, he died at the age of 84. His wife Asenath survived him to the age of 95. They are both interred in Green Hills Cemetery, the bodies having been moved at some point from their original resting places, probably in the Pioneer Cemetery.

————————————————————————-

Surveying the Dryden Military Lots Part 6 – Finished!

By David Waterman (from August 2021 newsletter)

After failing to complete the survey of Dryden in 1790, John Konkle’s relationship with Moses DeWitt continued to deteriorate. On January 24th, 1791, he wrote:

I am very uneasy on acc’t of being frustrated in my Designs, (to wit) not Compleating the Township of Dryden – … as for the uncommon Early & Severe fall & winter Season is well known to your Self – hope therefore that you will not think hard of it – I will Endeavor to make a finish as Early as the Season will admit – I have taken great Pains to do the business accurately – I have Chained every foot of the Interscition Lines, which if I had omited, as others have I could have made a Compleat finnish.

Meanwhile, he was asking DeWitt for favors – first, to secure his land in Newtown (Elmira).

If I mistake not all Lands in Chemung are forfeited which are not Cleared out of the Office this Ensuing Spring – in Consequence wherof I have Sent you my Certifycate together with a Power of Attorney for you to act in my behalf.

Also, to be nominated for a government position.

Whereas there is Something of a Prospect of having this Country Laid off and Organized into a County – and a Number of Nominations has been made for the Several County offices but I have not understood of any application being made for the Office of Surrogate which is requirted in Every County although of no great Consequence at Present, But as I expect remaining in This Place it may be of Some Benefit in time to Come – and as I have been Somewhat Acquainted with the Nature of that Business, I should therefore be happy if you could Intercede for me with the Honorable the Council of appointments to fill that Station.

And Konkle wished DeWitt to hire him for surveying additional Military Tract Townships:

Wheras I have been Something unlucky about the Township I have undertaken – I should be glad to try another – Next Summer in order to mend the matter – and if agreeable to you and Major Hardenbergh – and reserve one of the Townsh’s for me, will be acknowledged as a great favor

Despite promises of punctuality, Konkle did not restart the Dryden survey until June, only completing it on July 2nd.

In haste I Embrace this opportunity to Inform you that I have made a finish of Dryden, I am Now about making the Field=Book, and Expect as Soon as I Can Possibly Compleat it to make a return of the Same to you.

But upon returning home to Newtown, he found over 1400 Seneca and Cayuga, men, women and children were camped along the riverbank and on the flats, 1/2 mile from his house. A treaty meeting had been planned to take place at Painted Post, but following a dry early summer, the Chemung River was too low to carry the flat bottomed boats full of supplies further up river. Food, gifts, and barrels of rum were unloaded at Newtown, and the meeting was relocated. The Iroquois, who had already been forced and coerced by New York State to give up most of their land in exchange for retaining some reservations within it, had many grievances and were unsure where the Federal government stood on State matters. George Washington wanted desperately to avoid any public confrontation with the Iroquois while in the process of negotiating with other tribes further west to peacefully give up other lands. Following instructions from Washington “to declare to them the friendly disposition of the Federal government towards them, and its readiness to extent protection to them on all needful occasions”, large quantities of merchandise had been given to the Indians as a token of “peace and unity”. Supplies included “four barrels of rum, one box of pipes, two kegs of tobacco, and one keg of spirits.” Also “three gross of large silver brooches with which to decorate the Indians.”

The Newtown meeting began June 21st and lasted about 3 weeks. There were speeches by many notable Native orators including Red Jacket, Farmers Brother, Big Tree, Fish Carrier, and Cornplanter. Col. Timothy Pickering, for the Federal side, comes off as surprisingly unaware of Iroquois culture for someone who had been captured as a child and lived as a Seneca for years before escaping. From Newtown, he wrote to his wife, seemingly astonished, that “they have sent a message that their ladies will make me a visit… I must receive them in the same manner as the chiefs.” He also wrote, “The Indians all appear to be well disposed, and were it not for their inordinate love of rum, they would be very easy to deal with;”

For John Konkle, the experience of drunken Indians in his neighborhood was terrifying, and he wrote to Moses DeWitt:

… I Should have been with you Before Now but [for?] the Indian Treaty &c. Being here made it So Defen[se req’d?] that I Could not leave home.

Was this the last straw for Moses DeWitt? Probably the camel’s back was already broken. Konkle would never get more work from DeWitt, who was also losing interest in his holdings in Newtown known as DeWittsville. His eyes were on a large tract of Onondaga land near Syracuse which would become the town of DeWitt.

And Simeon DeWitt, upon seeing Konkle’s survey work, abandoned the possibility of a canal through Dryden and concentrated on the future Erie Canal route, though he continued interest in Ithaca, eventually owning 1,932 acres there, including most of the erroneous surveyor Martinus Zelie’s tract. Yaple and the first settlers of Ithaca were displaced.

But John Konkle landed on his feet, as they say, becoming the town clerk for two years, and the first Postmaster of Elmira. The first meeting of Freemasons was held as his house, and he is described in Elmira history as “public spirited and influential”.

(Italicized passages from: DeWitt Family Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries)

——————————————–

Surveying the Dryden Military Lots Part 5 – A Race Against Time

By David Waterman (from April 2021 newsletter)

Now it was a race against time. New York legislators were pushing hard on the governor, DeWitt Clinton, to get promised bounty lands to the Revolutionary War veterans. Now nine years since Yorktown, the soldiers were getting old, dying, or acquiring other frontier lands. Simeon DeWitt, the surveyor general, needed to provide a map defining the lots before a lottery could be performed to give out titles. Moses DeWitt, Simeon’s hands-on survey manager and himself an active surveyor, had made it clear to John Konkle, the Dryden Township surveyor, that speed, not accuracy was needed going forward. Konkle’s team, which had just finished accurately sizing up Dryden, knew there was plenty of leeway in the oversized township for the subdivision to be somewhat unequal and no soldier would get less than the 600 acres promised. In fact, the average soldier would get about 50 acres excess land.

Konkle’s field-book pretends every lot boundary line is exactly 77 chains, 46 links long, the length of a side of a 600 acre square. The actual lengths were not recorded, nor was the order in which the lines were walked. Marking lot lines with tree blazes and writing descriptions of the lot features were the important tasks for Konkle. These descriptions could be used to estimate the value of the lots, which varied considerably since they existed in a grid pattern lacking any relationship to topography. Many of the soldiers would quickly put their lands on the open market, and insiders with this information could profit greatly from it.

Four dates are given in the field-book, indicating starts of periods in which work was performed. The first line walked was the South bounds of lot 81. Beginning on the west boundary of the town, and facing “as the Needle pointed on the 24th of September 1790 Magnetic East”, they crossed “a Dry brook bearing SW’ly, the Owego Road” (now Route 79), “timbered chiefly with oak”, and the land “good but something stony”. Next there was “a Spring Drain in a Deep gully”, followed by “Rising ground Chief Timbered pine, a large valley S’ly” with “level land thick Under brush“. This typifies the level of description given for each and all of the lot lines of the Dryden Township. A copy of John Konkle’s field-book is kept at the Southworth Homestead where a docent can help you look up places of personal interest to see their 1790-91 description, whenever the facility is open.

There are a few interesting tidbits in the field-book, though most of the descriptions are of hills, water courses, land quality and lumber types. There are no mentions of Indian trails crossed, which would have been interesting, but near the South line of lot 73, Konkle tells of an “Indian Sugar Works”. Iroquois Natives harvested maple sap long before Europeans arrived, by using bark spouts and extracting excess water by setting the sap out to freeze at night. However, long before 1797, they would have acquired and been using the same tools as whites.

Konkle’s base camp was located near the place where the subdividing began, conveniently close to the road home or to Hinepaugh’s Mill for supplies. He wanted to do the southern, hilly parts of Dryden first, before the weather worsened, making walking the hills treacherous. The steep hills made it difficult to level the surveying equipment and some lines in Southern Dryden were pretty far off course. On the Eastbounds of lot 71, Konkle “entered a bawld hill (so called by the people of Cyuga)”. This was the hill between Genung Rd. and Quarry Rd., not to be confused with Bald Hill in Caroline. During the later years of native occupation, when Cayugas possessed some horses for traveling, the tops of some hills near trails were burned off to allow grasses to grow for grazing. As a result, several hills in Cayuga controlled areas are or have once been called bald.

Correspondences during the time of the survey indicate a deteriorating relationship between John Konkle and Moses DeWitt. DeWitt visited Konkle’s home in Newtown (Elmira), looking for a lost letter and map and later, while in Elmira, he checked some of Konkle’s other work and found a surveying error.

After responding with excuses and promises to do better, it was hard for John Konkle to finally give up and write the following letter:

Owego Dec. 22nd. 1790

Dear Sir/

Offer my Respects to you – I am under the disagreable Nescessity to Inform you that winter Set in about six days too soon for me to make a finnish of the Town of Dryden – after you left the Cayuga, I got out of Provission and Could get no Supply there, and I had to Send to Newtown – and at the mean Time winter approached to That began that it was not in my Power to Compleat the work – But as Soon as the Weather Moderates and the most part of the snow gone, I will Endeavor to accomplish the work and make a return of the field-Book as Quick as Possible.

I had made a map & field-Book of the Several Locations which I Surveyed for Coll’ & others whilst I was at the head of the Lake and left it in the care of Mr. Hinsbaugh but he neglected to give them to you – and afterward I Sent them to Newtown expecting you to be there – But as I have not got them with me here I will Send them By the first Oppertunity – I remain with respect your Humble Servant Jno. Konkle

P.S. I will Endeavor to make a return of Dryden field-Book before you leave N. York, and hope that you and Maj’r Hardenbergh won’t think hard of my not making a finish as Soon as Expected – I laboured under just disadvantages on accn’t of getting Provision and the weather was Excessive bad for the most part of the time I was out.

(Quoted passages from: DeWitt Family Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries)

Surveying the Dryden Military Lots By David Waterman (From October 2020 Newsletter)

Part 4 – Sizing Up The Township

At the end of part 3, John Konkle’s survey team had spent a day running most of a new northern boundary for Dryden, four chains south of an erroneous line previously run by Martinus Zielie. They had spent the night south of today’s McLean, near their 9th mile tree (which I mistakenly called the ten mile tree). The team continued measuring eastward in the morning, starting from the 9th mile tree, still wondering how much larger the Dryden township would be. Immediately, they were wading through an “older swamp” which stretched on for 400 yards. Out of it, they entered “Rough, Poor, Cold Land chiefly hemlock Timbered“. At 550 yards out, they crossed a “large fine spring Brook [which] runs South’ly” (Fall Creek near its source.) Then, at 925 yards, they “Entered a Cramberry Swamp (Nearly Round), run through the middle of it“. Emerging 330 yards later, they “Struck Cap’n Johns North Line run from the South Bounds to the head of the Scaniateless, 10 Ch. 58 Links North of his 10 Miles Tree.” This line defined the eastern boundary of Dryden so they set a stake there, and blazed a large black ash tree on four sides to identify the common intersection of the four townships named Locke, Homer, Dryden and Virgil.

There has never been another survey of the town of Dryden since 1790-91. The official town map does not indicate dimensions or GPS locations for its corners. Our Town Clerk suggested I might look up individual property surveys and add them up to get a number to check against Konkle’s measurement, but I decided to simply use Google Earth, which may have some systematic errors of its own. Konkle’s measurement of the width of the town totals up to 9.71 miles. On Google Earth I measured 9.83 miles. The difference of 1.3% is remarkably close, considering the process. The work was soon over on that day, since there was only the one tree to locate and blaze. The team walked back to Ludlowville, arriving by early evening, and could take Sunday off.

The cranberry swamp they had found was the only one of its kind that Konkle would describe in his Dryden Survey field-book. Today this bog is part of a Cornell Botanic Gardens Natural Area, and said to still contain some wild cranberries. For several thousand years before European contact, the Iroquois population of upstate New York was numerous. Any and all local sources of special foods and pharmaceuticals like this were well known and encouraged or tended in certain ways. The cranberry growth would likely have been dense, widespread and healthy. By the time John Konkle walked through it in 1790, however, the Iroquois population had been decimated and their ancient culture was in shambles. Remote satellite resources such as this bog would likely have been abandoned for two or three generations. Still this spot was thriving as a dedicated, round cranberry bog. Seven more generations have passed since then yet now, protected, some cranberries remain.

Monday morning the team went back to Moses Dewitt’s stake at the northwest corner of the township, this time to head south. This leg of the survey would be problematic because of Zielie’s erroneous measurements. The problem had been somewhat corrected by the 4 chains relocation of Dryden’s northern border, but the southeastern area of Milton Township, now Lansing, near Moses’ base camp, had already been subdivided and the trees blazed making further correction impossible. Any survey rework would have been political suicide, as the whole Military Tract endeavor was already way behind the New York legislature’s expectations, nine years after Yorktown. In his field-book, Konkle recorded an official figure of 345 chains down to the Milton/Ulysses border. A Google Earth measurement from Dryden’s northwest corner to Lansing’s southeast corner is 25 chains greater than that. The 4 chains correction had only reduced Zielie’s error from 8.4% to 7.2%. While traversing that erroneous segment, Konkle’s team would make no measurements. Work went fast just walking the line and describing the topography, noting brooks, swamps, and foliage.

After they passed the blazed tree which indicated the beginning of Ulyses, the team began measuring again, just the total distance without blazing any trees, which would have created further evidence of the cover-up. Continuing south, Konkle noted crossing “the fall Creek“, “the Brook that comes down by Mr. Hindpaw’s” (now Cascadilla creek), the “road leading from the head of the Lake to Owego” (now Route 79) and “a large Creek the inlet of the Lake” (now Six Mile Creek).

At 455 chains, 85 links, they reached the southern limit of the Military Tract. It was delineated by a line that Moses Dewitt himself had run eastward from the southern tip of Seneca lake in the previous year, with trees marked each mile from the lake. Konkle’s team “struck the line at 23 ch 39 L E of Moses 21 mile tree“. From this point there would be no more precise measuring nor tree blazing required, so most of the team headed back north along the nearby Owego Road to a place where they would be setting up a new base camp that would be more convenient for the future subdividing task.

Now heading East along Dryden’s southern border, Konkle referred to Moses’ mile numbers to situate his field-book descriptions of the land. Eleven chains past mile 30 he once again arrived at “Cap’n Johns North Line“, Dryden’s Eastern border. The total width of Dryden’s Southern border, as previously measured by Moses DeWitt, was about 10 chains greater than Konkle’s measurement of the northern border. About half of this difference is to be expected due to the convergence of magnetic lines as they approach the pole, so we can conclude that John Konkle’s surveying precision was within 1.4% agreement with Moses Dewitt’s work.

While following Captain John’s line of blazed trees north from Moses DeWitt’s line, John Konkle’s descriptions of foliage became very brief. Now he had all the data he needed for planning the subdivision of the township. It was a hurried 10 miles and 220 yards up to the northeast corner stake he had set the previous week, then a quick walk back to Ludlowville to confer with Moses DeWitt on subdivision plans.

(Quoted passages from: DeWitt Family Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries)

Surveying the Dryden Military Lots By David Waterman (From March 2020 Newsletter)

Part 3 – Beginning The Survey

I must apologize, having discovered an error in my timeline. The interaction between John Konkle and Peter Hinepaugh detailed in part 2 did not take place for another month. The letter Konkle left at Hinepaugh’s with his other paperwork is dated October 29.

The corrected timeline says it was immediate, probably the very next day after signing on with Moses DeWitt and receiving an advance for supplies, that John Konkle, with axmen and chain-bearers, departed Moses’ base camp near Ludlowville to begin the Dryden Township survey. They headed east on a Cayuga footpath, now route 34B, carrying their work gear and sleeping blankets. It was Friday, September 17th, peak autumn foliage time in 1790, a few weeks earlier than today with the Northern Hemisphere’s “Little Ice Age” still ongoing. About five miles in, they reached the western boundary of Dryden. A marked trail led directly north another mile from there to a stake set earlier in the year by Moses DeWitt, indicating the northwest corner of Dryden, where Konkle’s survey work was to begin. Assuming they got an early start that morning, the team could have been there by ten o’clock. Brush had grown up around the stake since it was driven, and the axmen set about clearing a large circle and blazing the trees all around facing it. Page 1 of John Konkle’s survey field-book outlines multiple confirmations that the work would begin in the right place:

“Beginning at a Stake in the East bounds of Township No 17. 345 Ch. (with one chain Allowance) from the S.E. Corner thereof, 33. Chains North from the Corner of lot No 85 & 89 in Township No 17 made by Mr. Hartt, 3 Ch. South of a fine large Brook run’g westerly, 4 ch. South of one of Cap’n Zeilies (pretended) Township lines & 7 links west from a black ash tree Marked on the S.E. side N.W cor.r 1790 Township No 23 and on the N.E. side S.W. cor.r Townsh’p No 18.”

From DeWitt’s stake, Konkle’s crew was to define a new northern boundary for Dryden, which would be “run from thence as the needle points East” and located 4 chains (88 yards) south of Zeilies “pretended” line. That word, by the way, carried no playful connotation in 1790, only pretense for willful gain, as in “pretender to the crown”.

While marking the new boundary, the team would also be measuring the width of the Dryden township, which was oversized, as were all the townships. Simeon DeWitt, the Surveyor General, had given himself some necessary leeway in defining the 23 townships, each at least 60,000 acres, as square and equal as possible, and fitting them in between the finger lakes and reservations for Cayugas, Onondagas, and Oneidas. In doing so, he had drawn lines south from the tips of Owasco and Skaneateles Lakes which defined Dryden’s east and west borders. They would be slightly over ten miles apart.

John Konkle spiked one end of the Gunter’s chain to the ground at the starting stake and positioned his tripod above the spike. He mounted his compass, rotated it to Magnetic East and peered through slits, motioning to the chain-bearer to move left or right in order to stay on course, as the chain was extended to its full 22 yards length. Axmen helped by cutting brush and moving fallen branches. When tree trunks got in the way, the chain could be snaked slightly to pass by without causing much error, but the compass view was blocked, so the tripod and compass were carefully repositioned further up the chain. Whenever the line went up or down a significant slope, the surveyor needed to mount and level a clinometer on the tripod and measure the slope angle. Then, using trigonometric tables, he calculated a hypotenusal adjustment, in links, to correct for the foreshortening of the chain as seen from above. Each time the chain was extended out 80 times and the accumulated adjustment, in links, added to the distance, they drove a mile marker stake. Axmen blazed the closest large tree with the mile number. Surveying and marking, the team probably advanced at about 1-1/4 miles per hour at best.

Meanwhile, Konkle also took notes to provide “description of the Courses and Distances of Brooks, Soil and Timber &c” in the field-book. Along the northern boundary of Dryden he noted beech, hemlock, maple, linden, and white pine. He identified good soil in some areas and middling soil or swamps in other places. The information contained in the surveyor’s field-book, when completed, would enable a person to estimate the value of each lot, information that would not be available to the soldiers, who were to be dealt the lots randomly. The value of this knowledge to land speculators, as lots went on the market, was astounding and Simeon DeWitt, Moses DeWitt, Major Hardenbergh, family members and allies would profit greatly from it. John Konkle himself would soon have intimate knowledge of the hundred lots of Dryden, which might also be turned to some profit for him long before being paid for the survey.

If they marked the tenth mile tree that day, the survey team was on a rise southeast of today’s McLean. With the sun sinking down and wetland ahead, not knowing how soon they would hit the eastern line of the township, the men needed to set up camp, collect wood and start a campfire. John Konkle reviewed and edited his notes. He must have been feeling elated. His letter seeking this job, had disclosed, “It has been my lot to deal with Dishonest People, whereby I was greatly Injured”. Something bad had happened in Sussex County, NJ after the war to make him take refuge in Newtown, NY, but now he was working with the most powerful families in New York State. His life seemed turned around.

(Quoted passages from: DeWitt Family Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries)

———————————————————————————————-

Surveying The Dryden Military Lots by David Waterman (From November 2019 Newsletter)

Part 2 – Taking Care of Business

It was September 16, 1790, by the time John Konkle signed the agreement with Moses DeWitt, to subdivide the Dryden Township. Though he had arrived at Moses’ base-camp on the East shore of Cayuga Lake, near present day Ludlowville, in early August, he had made only a verbal commitment to do the work, “because of Maj. Hardenbergh not being Present”, according to Moses’ log-book. Major Abraham Hardenbergh was Moses DeWitt’s partner in the Military Tract surveying project. He was not a DeWitt or a Clinton, but he was an in-law. The veteran soldier added necessary muscle when protesting Indians or squatters needed to be strong-armed to keep the survey going. It is curious why Konkle was so concerned and why DeWitt allowed the six week delay. In the interim time, Moses had given him another surveying task to do, and now he needed to gather up his notes, write a field-book and make a map for Moses before the Dryden subdividing task could finally commence.

By this time John Konkle knew the men camped out around the base-camp looking for work, and he could quickly assemble a surveying team. He probably needed two chain bearers, two or three axe-men, and a couple of other helpers for cooking, moving and setting up camp, and other odd jobs. The crew could make preparations while John completed his paperwork. DeWitt and Hardenbergh occupied DeWitt’s survey cabin, preparing for a field trip of their own and would soon be leaving. John needed a dry place to ink his map, and a trusted person to hold onto it until Moses returned. He decided to spend the night with Peter Hinepaugh, at the head of the lake. Small sailboats waited on shore below the base-camp, offering rides North to the trail toward Albany, or South to the head of the lake. If the wind cooperated, it was a faster and more pleasant way to travel to Hinepaugh’s than walking the East Shore Trail.

Peter Hinepaugh’s mill was located at the bottom of the falls of Cascadilla Creek, known then as Hinepaugh’s Mill Creek. It marked the start of the road to Owego, and first leg home for both Moses DeWitt and John Konkle. A small log cabin nearby housed Peter and his wife and five children, and they also found room to put up guests. Konkle could use this dry place for his work, then trust Hinepaugh to give the materials to DeWitt when he came through.

Hinepaugh and his two half brothers, Jacob Yaple and Issac Dumonde, had just finished their third summer at Cayuga lake, planting crops in former Native clearings and building four log cabins and the gristmill. Last fall they had brought in their families, in all four men, four women and twelve children, who were the very first families to settle in Ithaca. The grueling two month long trip from Owego for them had involved a widening of the “Warriors’ Trail” into a road to enable their ox carts, loaded with tools, supplies and toddler children to pass. Soldiers and refugees, veterans of the Clinton/Sullivan campaign, they had seen a promised land at the head of Cayuga Lake.

The family migration to Cayuga Lake had been Peter Hinepaugh’s idea. Now he feared it might all be for naught. Their applications for deeds to the land had not yet been approved, and New York’s legislature was considering settler families in the conquered Iroquois homelands to be “squatters”. Ever since the previous year, when Moses had stayed at the cabin while redoing a survey of land patented to Martinus Zielie, Peter had been imploring Moses for help obtaining his patent. Understandably beside himself, he wanted to quiz John about Moses’ intentions. Why had Zielie’s 1400 acres adjacent to Peter’s been approved, but his 400 acre tract was in limbo? John Konkle certainly wished he was tight enough with the powerful young DeWitt to have known his plans, but he did not. He did know something about Martinus Zielie, though. The DeWitts were extremely angry with him. Not only had his plot been much larger than it was supposed to be, but Zielie’s surveyor had also done erroneous work for the Military Tract, affecting township boundaries of Ulysses, Milton, Dryden, and Locke. Milton Township was already mostly subdivided, so a correction Konkle would be making would only partially correct the problem. The issues were costs, delays and political fallout.

There was another question which surely crossed Hinepaugh’s mind. How did John Konkle get his land in Chemung? That area, south of the Military Tract, was going to various deserving veterans who were not on the bounty land list. These included generals and career officers, men who ran gunpowder factories, etc. and spies. Where did John Konkle fit in? Maybe John had ready answers to questions about his war record, but maybe he demurred. Better to think of toworrow’s boat trip back down the lake, and get some sleep.

Both men probably felt troubled that night. Konkle wondering if he should not have spilled the beans on Zielie, though maybe it was necessary to deflect questions about himself. Indeed, how could he explain being awarded his land in Newtown, next to General Clinton’s son Charles, and Col. Henry Wisner’s son Jeffery? And why would he have taken Annie and their three children from New Jersey to the uninhabited Chemung wilderness after the war anyway? Begging for work, he had written Moses, “I do not know how to support my family, I have no farming utensils.” There is more to the story. Hinepaugh could not have known it, but right beside John Konkle’s plot in Newtown, an identical plot of 197 acres was designated for Adam Konkle, his cousin. In 1792, Adam will apply to the British for “United Empire Loyalist” status, be awarded 200 acres in Beamsville, Ontario and emigrate there. How could John’s cousin Adam Konkle be awarded land by both sides of the conflict? Maybe more will come up as the survey begins.

————————————————————————-

Surveying The Dryden Military Lots by David Waterman (From August 2019 Newsletter)

Part 1 – John Konkle Gets the Job

John Konkle was the surveyor who marked out the Dryden Military Lots in 1790-91. He lived in Elmira, NY, then called Newtown. His log home was on lot #85, east of Newtown Creek. The Konkle family had been one of the first to settle in Elmira two years earlier and John worked surveying lots for other people. Their home in Newtown doubled as an inn, with a liquor license issued by the town of Chemung in 1790. Surveyor work was sporadic and seasonal, sometimes taking John away from home for long periods of time, and his wife Annie probably did most of the inn-keeping work while taking care of their three children, then ages 10, 6, and 4. Newtown had been a Cayuga and mixed Iroquois town named Kannawalohalla (head on a pole) before Generals Clinton and Sullivan brought their armies through in 1779. Sullivan himself renamed it Newtown, and the Newtown battle site, scene of the only major engagement of the campaign, was 6 miles from where the Konkle’s made their home. By 1790 some Natives had returned and were living peacefully at the fringes of the rapidly filling town.

Less than a mile from Konkle’s land, a 700 acre tract was called DeWittsburgh, after Moses DeWitt, who owned the land but never lived there. Moses was a young cousin of Simeon DeWitt, the Surveyor General of New York, who was a nephew of DeWitt Clinton, the Governor of the state, who in turn was son of James Clinton, the Clinton/Sullivan general. Moses was a surveyor, like John Konkle, and employed in 1790 by his cousin Simeon as field-manager on a huge project for their uncle, the Governor. They were dividing 4 million acres of Iroquois homeland into 26 townships, as square as possible, each subdivided into 100 square lots of a square mile each, to be given by lottery to a list of deserving revolutionary soldiers.

John Konkle met with Moses DeWitt at Wyncoop’s Inn in Newtown near Christmas of 1789, but he did not get a chance to discuss some important business with him, so on January 2nd he wrote a letter. The letter informed Moses of “Male Contents of this place [who] are determined to carry their designs into execution against the Commissioners &c.” The commissioners had been authorized to settle land disputes between settlers of the Chemung area. One of the three commissioners was General Clinton, who had personally taught both Moses and Simeon their surveying skills. John’s letter asked Moses to “intercede in my behalf for some of the land whereon I now live…and I will reward you for it to your satisfaction.” He added a postscript, “And if any Business is to be done in this place I should be happy to serve you in any thing that Laid in my power.” Thus began a working relationship between the 24 year old Moses DeWitt and 33 year old John Konkle. The commissioners subsequently awarded Konkle 297 acres where he had originally settled.

John Konkle and Moses DeWitt both hailed from distinguished families. Konkle’s great grandfather had been a wealthy German and a man of letters, when he landed in Philadelphia in 1748 at age 66 with two sons and their wives. Though he had traveled in style, the old man was appalled at the conditions encountered by other emigrating Germans packed in the ship. He wrote a long and scathing letter about the horrors of the passage and human trafficking of Germans being indentured. This letter was published in Germany and virtually shut down German emigration to America for years. These Konkles acquired a large tract of frontier land in the New Jersey part of the Minisink Valley, which became the predominantly German community of Hardwick, Sussex County. German immigrants were largely pacifist or loyalist sympathizers during the revolution, having come to America to escape the chaos of civil war back home. John’s father ultimately emigrated to Canada. John stayed out of the war, marrying Annie Wurtz in Sussex County at its height in 1779. Moses DeWitt’s great grandfather had been the chief of an Irish extended family, who paid the passage for 93 people on their 1729 crossing, following two years of famine in Ireland. In his log he chronicled 98 deaths during the May 1st to Oct 4th voyage, many of whom were his people. Moses was the oldest son of Jacob Rutsen DeWitt of Mamascotting, in the NY portion of the Minisink Valley. DeWitt family fortunes grew with their patriotic war efforts, though Moses DeWitt himself was too young to have fought.

By the summer of 1790, Moses had marked the peripheries of the 23 Military Tract townships. Then, from his base camp on the east shore of Cayuga Lake, he began hiring surveyors to subdivide them. Konkle sent DeWitt another letter in July. It said, “I am informed with pleasure that you have arrived at the Lakes, in order to Survey the Soldier Land, and likewise that you are in want of more Surveyors. I have an Extra ordinary Set of Instruments and I am in no kind of business at Present, and unless I Can get to do Something in that Line I do not know how to support my family [IF you will] Employ me in that line I will Endeavour for to give Satisfaction as much as is in me lies, and I shall be able to procure hands for chainbearers &c. in this place.” John got the job. On September 16th, Moses wrote in his field notebook: “Mr. John Konkle Entered into written Articles of Agreement for the Subdividing Township No. 23. [Dryden] for 160£. payable in two years. if not then paid for 190£. and wait until the same can be Collected by Law – advan’d some provisions & Cash as part pay.” The survey of Dryden would now begin.

(Quoted passages from: DeWitt Family Papers, Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries)

————————————————————————–

The Revolutionary Soldier Who Did Not Want Dryden Lot 39 – (FROM MARCH 2018 NEWSLETTER)

By David Waterman

Dryden Lot 39 is a square mile of land with one corner resting on the village four corners intersection. It extends from there, a mile each way North past the churches and the Southworth Homestead, and East toward Virgil. Edward Griswold settled on this lot 39 in about 1802, a year after the Amos Sweet log cabin on the same lot became abandoned. Mr. Griswold was a large presence in early Dryden Village history, credited with a host of generous acts, as detailed in Goodrich’s “Centennial History of Dryden” (p.77), in which he is declared “Father of the Village of Dryden.” Griswold did not obtain this land from Military Tract balloting, though he fought in the Revolutionary War. He did his part for Connecticut, not New York. The Military Tract balloting, finally accomplished in 1791, gave Dryden Lot39 to one Bartholomew Vanderburgh, Ens. 2nd NY Regiment, who had really no need for frontier land. For the Village of Dryden, it seems this turn of events was fortunate. Just think how different Dryden village’s early history could have been.

Bartholomew Vanderburgh was born in 1753, the second son of a Dutchess County founding family. His father, James Vanderburgh, had built the first substantial house in the Beekman area, in which he ran an Inn. In the revolution, the home was used as a supply depot for the Americans. James commanded the fifth regiment of Beekman County Militia and had 40 men to guard the stores. His Inn became a favorite, secure stopping place for George Washington, who preferred to stop there whenever he traveled through Dutchess County.

The son, Bartholomew, joined the American cause in May of 1778, he being then 21. Complaints were soon lodged to General Clinton that Vanderburgh had previously joined one company as an enlisted man, before joining a different company where he would be an officer. A letter questioned whether he had given back his first signing bonus.

In early summer of 1779, Ens. Vanderburgh was home at his father’s Inn, and his father was not, when a French officer helping the Americans, and men under his command were staying there. Bartholomew somehow insulted the French officer, with some anti-French sentiments. The French officer had Bartholomew clapped in irons in the cellar of his father’s house, where he allegedly beat and frightened him, and would not allow any of his family to visit him, until Bartholomew begged for pardon.

When his father found out about the incident, he wrote a letter of complaint to George Washington. Armand was charged with the offences mentioned above, as well as various instances of knocking people’s hats off their heads, “being a breach of the 1st. Article 9th. Section of the Articles of War.” Then Lieutenant Colonel Armand-Tuffin wrote a lengthy and vitriolic letter to his friend, Alexander Hamilton, to seek help in his defense. In it, he stated that “Mr. Vanderburgh is a contemptuous person, not because his son, who is the person who insulted me, but because he holds the insult of his son as if he had done a very good deed.” He goes on, “I am French, they hate us, they like to hang us here in this country”, and then he characterized Americans as “a people too young yet to understand the political skill necessary to hide their natural hate.” The letter did not succeed in obtaining Hamilton’s assistance, and Armand lost his commission.

Bartholomew served in the 5th NY Regiment during the Clinton/Sullivan Campaign, which was tasked with the elimination of Iroquois towns and food supplies in Upstate New York. His widow, in her deposition for a pension, stated that she remembered Bartholomew talking about “going against the Indians”, but she could not remember any details. After the war, Bartholomew moved back onto his father’s farm. His life after the war was not entirely without incident. In 1788 he was found to be in possession of someone else’s horse for which he refused to pay and was sued. At some point he secretly married, against his father’s will. They kept the marriage and their baby a secret and did not “officially” marry until much later, 1792. Bartholomew died in 1796 at the age of 43, one year before Amos Sweet came to Dryden, and is buried on his father’s farm.

As an officer, Ens.. Vanderburgh was entitled to two Military Tract bounty lots. The other lot he drew was Hector lot 73, a beautiful, hilltop spot overlooking Seneca Lake, west of Mecklenburg. He did not want that one either.

Life in Dryden in the 40s

By Betsey Van Sickle (from March 2017 newsletter)

I moved to Dryden at the age of 3 in 1944 when my father went into the Navy during WWII. My mother was Genevieve Wood Van Sickle, and we moved into the Rockwell House with her father and my grandfather, Walter Wood. He was living there alone since his mother, Georgianna Thomas Wood Rockwell, died in 1939. Georgianna had lived at the Rockwell House since the 1880s when she had married Melvin Rockwell, and had three more sons, Saunders, Chester and George.

But this is about me and Dryden. In the 1940s Dryden was transitioning from a lazy, quiet, farm community into a “bedroom community.” People started to move in and build houses on many of the dirt roads surrounding the village: roads I used to ride my bike on in later years.

I can still remember the farmers coming to town with horse-drawn wagons full of whatever to take to the mill where the cemetery place is now. It was a busy mill, ground flour, corn, wheat from dawn to dusk. The train often stopped there or at the train station a few yards down the track where Brecht’s Towing is now. The train service used to be passenger as well as freight. I was very interested in trains, and every day I would ride my tricycle down to wave at the engineer as the train rolled by. It was an exciting time. I believe the only passenger service still in existence at the time was the Black Diamond which went to Ithaca and north to Auburn.

One major event in the village was “Old Home Day” which was in July or August and sponsored by the firemen. It is very similar to the Dairy Day we have now, except there was a carnival and beer tent at the end of Lewis Street. The parade went from west to east. I marched in it in 1958 as a drum majorette.

In those days, the village was a very active social place with many organizations and clubs. Almost everyone belonged to one or two and a church. My mother was in two evening bridge clubs. My father was in many clubs. Most women did not work, so they enjoyed their evening clubs. In the past few years, these clubs and organizations have dwindled considerably due to women working, family issues, television, electronic media. It is difficult to get people to come out to a function in the evening now.

People prided themselves on their homes: keeping the lawn mown, planting flowers and shrubs, having pets, painting barns and fences. I have to mention dogs and cats. Dogs were allowed to roam free and were all over the place. Also most people did not neuter their animals. I remember a dog named “Squeak” who belong to the Wood family on Lewis Street. He would always run to our back door for a treat with or without his owner. Often the Woods would call us to ask if Squeak was at my house. We always had cats to keep the mice away. They were not the pets we know and cherish today. These cats were outside most of the time just to come in for food. I had a pet cat my father named Blacktop who was an indoor-outdoor cat. He lived about 20 years.

Children played a lot in their yards. Hide and seek, tag, red rover, etc. No television. I used to climb an apple tree back of our barn and no one could find me. I also had pet turtles; the ones you got in the dime store with painted backs. I had two: Reddy and Bluey. My first life’s tragedy occurred with these little guys. A little girl from next door, about 3 at the time, picked up Reddy and bit his head off! I remember screaming at her and rushing in the house and showed my mother. I do not know what mother did with the beheaded creature. I was about 5-6 at the time. I think we buried it in the garden.

Other times we played in the house. I had a special extra room which was made into my “playroom” where all my toys were. I played in that room until I was 11 or 12. I had friends who came, but I was usually alone. I had a small town, a farm, a doll house, and a fort which I combined to make a daily plan for everyone in the town for each day. I also had an electric train that ran through the town. I don’t know where the time went but all of a sudden I was 12 and was losing interest in make believe people. I did continue to play the board games with girlfriends. I see many are still here: Monopoly, Finance, Chinese checkers, Scrabble.

Visiting the Southworth House

My Aunt Becky, my mother’s sister, lived at Southworth House with her husband George and father, John and step mother, Florence. Aunt Becky is better known as Sarah Rebecca Wood Southworth Simpson but to a 4 year old this was not important. She was and always will be, Aunt Becky. Her husband, George and my dad were in the service fighting for our country. My dad was in the Navy at San Diego and George in the Pacific somewhere. George was part of what they called “mop up campaigns.” My dad ran the Navy Base newspaper, The Drydock. He always told me I should go to San Diego and I did in Fall 2016. It was a very exciting and beautiful place.

Being a little girl at the Southworth House, I played with the lovely doll house and colored. Beck’s two boys had not yet been born. One had, John, who had died after he was born. Mother and Beck and I would go on “shopping expeditions.” We would get in an old Ford roadster and go to Cortland or Ithaca. It was an all day affair. I liked it because I always got more toys and clothes. When we returned, we would eat dinner with John and Florence. Florence always asked me a lot of questions. I remember asking her questions but never got a good answer. John talked a lot about the stock market and the war in Europe. It was like a distant storm to me, a horrible storm I did not want to hear about. I was glad that my dad and uncle were in the other war.

The house then was much as it is now. Florence spent most of her time in the kitchen cooking. She did all the work there. She loved to bake bread and wonderful pies and cakes. After my father and uncle returned from the other war, a few months later my cousin George was born and my brother Peter a year later. I was so busy with my coloring books, books, toys, etc. that I never bothered to think how they got here.

I do remember Uncle John talking about President Roosevelt and something called Social Security he had just passed. People from that time forward would have money taken out of their pay and put away until they retired. John was retired, but seemed to think it was a great idea. A lot of people didn’t, especially Republicans. I actually thought it was a good idea and I was not a Republican or a Democrat.

I spent many happy days at Southworth House in its ante bellum elegance. I looked at all the paintings, the dishware, books, and was fascinated by all the elaborate pieces there. Uncle John had gone hunting from time to time, and there was a bear rug and a tiger rug up in the back of the house. I was scared of them. This part of my childhood sort of faded away, like a distant dream and I only recall faint glimmers of those lovely days. The whole world changed after the war.

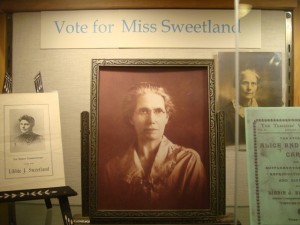

Libbie J Sweetland DTHS Exhibit (From June 2016 newsletter)

At a time when women didn’t even have the right to vote, Libbie Jayne Sweetland was elected District #2 School commissioner, the first woman to do so in Tompkins county, and a position she held for 10 years. In an open election, Miss Sweetland ran against her male opponent who was an incumbent. She won by a majority of 600.

Miss Sweetland published a book using the poetry of Phoebe and Alice Cary in teaching her classes, she took further studies at Cornell to augment her skills as a keen observer of the natural world. She used her limited resources to help others in the community. Many appreciated her letters of support and encouragement to the area WWII Service men stationed far from home.

“This is an age of great things, great thoughts, great inventions, and great events. New ideas are crowding out old… What was up-to-date in the closing years of the old century is rapidly being left behind in the opening years of the new. “To keep up with the race of events, we must possess the necessary means of progress, and of these means the best are books – books of reference, of information… “You must keep gathering Knowledge…”, The Twentieth Century Cyclopedia of Practical Information, published in 1901.

Libbie Jayne Sweetland, although born in the nineteenth century in 1869, was a perfect example of these words. Born at Dryden Lake, she received her education at Dryden High School, Cortland Normal School and Cornell University. She was a well-loved teacher at area schools and at Dryden. Libbie was a true educator, who encouraged her pupils in life skills through her love of reading. While attending the 1909 Teachers’ Association meeting, Commissioner Sweetland gave an address entitled, “The Value of Teaching Good Literature.” She was a founding member of the Dryden Literary Club in 1907. The motto of the organization was, “there is an art of reading, as well as an art of thinking and an art of writing.” On December 31, 1908, Miss Sweetland opened the literary program with the conversation topic, “George Elliott.”

She used her appreciation of nature to inspire curiosity in all things. Several of her specimens are included in the Cornell Liberty Hyde Bailey Horatorium database. She offered premiums referring to nature in the school department at the tremendously popular Dryden Agricultural Fair.

Libbie J Sweetland was a true educator who encouraged her students, the educational community, service men, fellow Literary Club members, and all who knew her “to keep gathering knowledge.” She was an educator, most admirable.

My Life in the Flower Gardens (from March 2016 newsletter)

By Shirley (VanPelt) Otis Price

I remember my mother’s flower gardens very vividly. She had a rock garden shaped like a pie cut in four pieces with flat stones dividing the four pieces and a walkway made of flat stones to the garden. My father hauled the stones and built the garden for my mother. It was a shade garden under two very large pine trees. There were lily of the valley along the walkway, and chives that I remember tasting. My brothers and I would play tag jumping from rock to rock while my mother was weeding or planting something new. I don’t remember my mother disciplining us when we had a misstep and trounced on her plants, which happened often. My father built a trellis with benches at the beginning of the walkway and planted clematis on each side of it. Over the years the clematis grew so that it covered the entire trellis. She also had a wire trellis outside of her kitchen window that was about 100 feet long and 6 feet high with red and white old fashion climbing roses. Alongside of the roses my mother planted daffodils, narcissus, tulips, crocuses, snowdrops and hyacinths that bloomed every spring. At the end of the trellis outside her window was a huge red bleeding heart plant that would get bigger every year.

In the front lawn she had a row of peonies, at least 10-12 plants, which multiplied every year and my mother would wrap string around them to keep them up. Alongside the row of the peonies she had planted more spring bulbs.

I remember my father planted a lily garden in front of the old shop. He loved the smell and sight of all the different lilies that he planted and weeded for many years in his retirement years. That section of the yard also grew current bushes and a huge asparagus patch. He also kept a ¼ acre vegetable garden that he shared with all of us.

It was in my heredity to love flowers and establish my own flower beds at my home. I love greeting each new bloom in the spring, the narcissus, the tulips, the crocuses, the Virginia bluebells, the hyacinths and the iris, than later as the perennials start to grow. I have neglected my beds the last couple of years due to keeping up with the lawn mowing of 4 acres. I am hopeful that this is the year to reclaim my beds. I have my special flowers that have been transplanted from other friends and family gardens. I have the climbing old fashion roses from my mother’s trellis that I dug up in the early 1970’s planted along my fence by the road. I also have the Japanese quince bushes along my fence transplanted from my parent’s bushes. I have many varies of peonies that were transplanted from my mother-in-law’s property that I placed along the railroad bank. I love the memories that these flowers give me because they were given to me by someone special. I planted hollyhock seeds by the outhouse hoping to have them grow so that I can show my grandchildren how to make dolls out of the blooms as my mother showed me as a child.

There is something therapeutic for me while working in my flower beds. Pulling weeds is very satisfying and when your life is complicated, this is a great time to think about what is important or not. It is also solitary, as you will notice that usually no one comes to help.

I almost made it to the Philadelphia Flower Show last year, but missed it due to a family illness. This year is the 100th year of National Parks and the flower show is going to be different park themes. Again I will be missing the show due to family, as I am going to LEGOLAND with my grandsons, which is the former Busch Gardens and I am told is full of flowers.

My favorite gardens are Longwood Gardens in Kennett Square Pennsylvania. They have 5 acres under solariums where there are full size trees growing with lawns and over 300 acres of outdoor gardens and trees and shrubs and ponds and a couple of tree houses. I have visited the gardens five times at different times of the year. There is always something different and I have yet to explore the entire gardens and look forward to return trips. They are only 4 ½ hours away and well worth the drive.

A Dog Howled All Day By Sandra Pugh (from Fall 2015)

In September 1943, Victor G. Fulkerson, my Dad and farm boy from West Dryden, joined the United States Marines. Three boys from West Dryden joined the Marine Corps in the same year – my Dad, Richard Niemi and Arnold Kannus. All three survived World War II.

Dad received training at Parris Island, South Carolina and Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. He was assigned to the 41st Replacement Battalion and deployed to the Pacific Theater. The replacement battalion joined the First Marine Division on Pavuvu in the Russell Islands. On September 15, 1944, the First Marine Division landed on Peleliu. Dad’s company was in the first wave ashore. His platoon got ashore with very few casualties. They moved inland to a dispersing area next to the airport. The next waves never got ashore.

Some of the worst fighting was at Bloody Nose Ridge. Several attempts to take the ridge failed. Colonel “Chesty” Puller commanded the 1st Marine Division. He ordered three companies to line up, one behind the other, and take the ridge at all costs. The companies took off in 10 minute intervals and took the ridge. By the time the fighting was over, approximately one company was left. Dad left Peleliu after 15 days and returned to Pavuvu. Dad had become an old Marine at the age of 18.

In November of 1944, training started with beach landings and long marches with full gear. This training lasted until the end of February 1945. Around March 1, the Division boarded a ship and left Pavuvu with no idea where they were going. The ship stopped after several days. Dad went up to the top deck to see what was going on. The sea was full of ships of all kinds – aircraft carriers, battle ships, destroyers, cruisers and troop ships. They were then briefed that they would be landing on Okinawa.

On April 1, 1945, the Marines and Army landed on Okinawa in a joint operation. The landing took place in the middle of the island. The objective was to cut the island in half. The Marines would go north and the Army south.

On May 10, 1945, Dad’s company had just taken a small ridge and were setting up for the night. He dug in with one of his friends from his original platoon. At this time there were only seven guys left from that platoon. At this point they were close to Shuri Castle and could see it in the distance. Sometime during the night a Japanese soldier got close enough to throw a yardstick mine into Dad’s foxhole. He and his friend jumped out just as it went off. Both of them were hit but got back in the foxhole and started throwing grenades.

The same day, almost 7,500 miles away on the farm in West Dryden, a dog howled all day. Grandma (Nellie Gibson Fulkerson) said Dad’s dog, Snooks, sat at the northeast corner of the farm house and howled all day long for no reason that she or Grandpa could determine. Days later they received a telegram from the Marine Corps saying Dad was wounded that day.

Dad recovered from his injuries and received a Purple Heart. He later re-enlisted to serve in the Korean War. We recently celebrated Dad’s 90th birthday with family and friends – he was born June 29, 1925.

Address

14 North Street

P.O. Box 69

Dryden, NY 13053

Contact

607-844-9209

drydennyhistory@gmail.com

Hours

Saturday, 10am - 1pm

Tuesdays, 10am - 1pm

Or by appointment

drawing by Cynthia Cantu

Mailing List

Send an email to drydennyhistory@gmail.com to be kept informed of upcoming events.